Terminale > Mission Bac LLCER Anglais > Mes sujets de bac > Arts et débats d’idées

ARTS ET DÉBATS D’IDÉES

Exercice d'application

Annales

-

Thème « Arts et débats d’idées »

1re partie - Synthèse

Prenez connaissance de la thématique ci-dessus et du dossier composé des documents A, B et C et traitez en anglais la consigne suivante (500 mots environ) :

Taking into account the specificities of the documents, analyse the ways in which language is used to raise awareness about free speech.

2e partie - Traduction

Translate the following passage from Document C into French. L’usage du dictionnaire unilingue non encyclopédique est autorisé."Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten. Already, in the Eleventh Edition1, we’re not far from that point. But the process will still be continuing long after you and I are dead. Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller."

1 the Eleventh Edition of the new dictionary of Newspeak

Document A

Neil Gaiman: Credo

What I believe.

I believe that it is difficult to kill an idea, because ideas are invisible and contagious, and they move fast.

I believe that you can set your own ideas against ideas you dislike. That you should be free to argue, explain, clarify, debate, offend, insult, rage, mock, sing, dramatise and deny.

I do not believe that burning, murdering, exploding people, smashing their heads with rocks (to let the bad ideas out), drowning them or even defeating them will work to contain ideas you do not like. Ideas spring up where you do not expect them, like weeds, and are as difficult to control.

I believe that repressing ideas spreads ideas.

I believe that people and books and newspapers are containers for ideas, but that burning the people will be as unsuccessful as firebombing the newspaper archives. It is already too late. It is always too late. The ideas are out, hiding behind people’s eyes, waiting in their thoughts. They can be whispered. They can be written on walls in the dead of night. They can be drawn.[...]

I believe you have every right to be perfectly certain that images of god or prophet or man are sacred and undefilable, just as I have the right to be certain of the sacredness of speech, of the sanctity of the right to mock, comment, to argue and to utter.

I believe I have the right to think and say the wrong things. I believe your remedy for that should be to argue with me or to ignore me, and that I should have the same remedy for the wrong things that you think.

I believe that you have the absolute right to think things that I find offensive, stupid, preposterous or dangerous, and that you have the right to speak, write, or distribute these things, and that I do not have the right to kill you, maim you, hurt you, or take away your liberty or property because I find your ideas threatening or insulting or downright disgusting. You probably think my ideas are pretty vile, too.

I believe that in the battle between guns and ideas, ideas will, eventually, win.

Because the ideas are invisible, and they linger, and, sometimes, they are even true. Eppur si muove: and yet it moves1.

1 Eppur si muove: Italian phrase attributed to the Italian mathematician Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) in 1633, after being forced by the Inquisition to withdraw his claim that the Earth moves around the sun.

Neil Gaiman, newstatesman.com, 29 May 2015

Document B

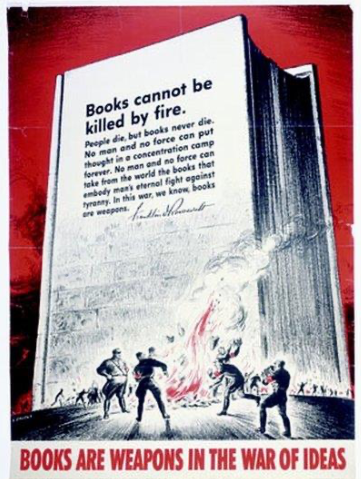

“Books cannot be killed by fire.

People die, but books never die. No man and no force can put thought into a concentration camp forever. No man and no force can take from the world the books that embody man’s eternal fight against tyranny. In this war, we know, books are weapons.”

Franklin D. Roosevelt1

1 Message from Franklin D. Roosevelt to the Booksellers of America, 6 May 1942

Poster, no. 7, 70 x 50 cm, Office of War Information, G. Broder, 1942

Document C

‘It’s a beautiful thing, the destruction of words. Of course the great wastage is in the verbs and adjectives, but there are hundreds of nouns that can be got rid of as well. It isn’t only the synonyms; there are also the antonyms. After all, what justification is there for a word which is simply the opposite of some other word? A word contains its opposite in itself. Take ‘good’, for instance. If you have a word like ‘good’, what need is there for a word like ‘bad’? ‘Ungood’ will do just as well—better, because it’s an exact opposite, which the other is not. Or again, if you want a stronger version of ‘good’, what sense is there in having a whole string of vague useless words like ‘excellent’ and ‘splendid’ and all the rest of them? ‘Plusgood’ covers the meaning, or ‘doubleplusgood’ if you want something stronger still. Of course we use those forms already, but in the final version of Newspeak1 there’ll be nothing else. In the end the whole notion of goodness and badness will be covered by only six words—in reality, only one word. Don’t you see the beauty of that, Winston?’ [...]

‘Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten. Already, in the Eleventh Edition2, we’re not far from that point. But the process will still be continuing long after you and I are dead. Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller. Even now, of course, there’s no reason or excuse for committing thoughtcrime. It’s merely a question of self-discipline, reality-control. But in the end there won’t be any need even for that. The Revolution will be complete when the language is perfect. Newspeak is Ingsoc and Ingsoc is Newspeak,’ he added with a sort of mystical satisfaction. ‘Has it ever occurred to you, Winston, that by the year 2050, at the very latest, not a single human being will be alive who could understand such a conversation as we are having now?’

1 Newspeak is the language created by English Socialism, better known as INGSOC (cf. l. 24), which is the political party of Oceania, a totalitarian super-state.

2 the Eleventh Edition of the new dictionary of NewspeakGeorge Orwell, 1984, 1949